Pruning the Shadows: Kapil Seshasayee's Music Against Caste in the Diaspora/ Prarthana Mitra/ Issue 02

Springing from the anti-racism protests in the US last summer, the dawning of a #DalitLivesMatter consciousness in the Indian diaspora has, among other things, brought into question the brown artist’s positionality and the role of culture in annihilating caste. Galvanising that growing movement, and dismantling brahmanical hegemonies with his bold confrontational music, is Glaswegian multi-instrumentalist and songwriter par excellence Kapil Seshasayee.

Historically, immigrants are known to stick together when they first settle in a foreign country. “But wherever a lot of Indians live together, caste structures inevitably work their way in,” Kapil tells me over a Zoom call last month. Our conversation arrives on the heels of a major tour and his new single “Hill Station Reprise” featuring American rapper Lil B. The last time we spoke was in the winter of 2020, around the launch of South Asian art collective Chalo’s compilation visibilising music from the region. That was also my first encounter with Kapil’s work.

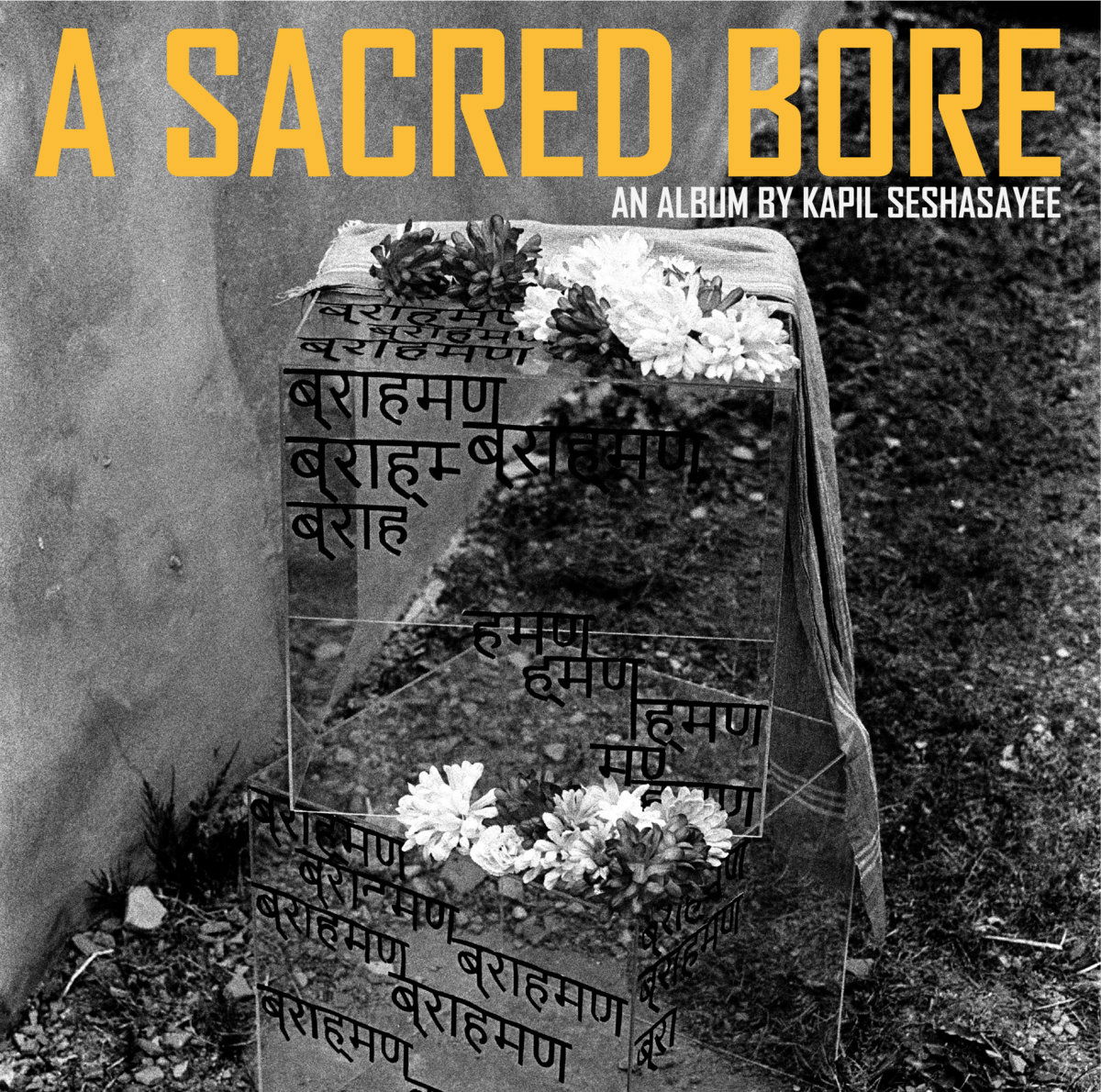

Writing about caste did not come naturally to the Indian-origin artist, who was born and brought up in a white neighbourhood in Scotland– away from the untouchability and segregation that he would occasionally witness on visits back home in Chennai. It wasn’t until college, when he overheard a casteist exchange between two diasporic women at a call centre he was working at, that he decided to do something about it. The incident also served as fodder for the title track embellishing his 2018 full-length, A Sacred Bore, the first in his trilogy of anti-caste records.

Raised away from any direct exposure to it, Carnatic music– like caste– eventually found its way into his craft too, albeit late and unannounced. “My father played a lot of music by Kadri Gopalnath, L. Subramaniam and U. Srinivas when I was growing up. You can hear the tanpura/veena in the way I tune and play the guitar!”

Back in Chennai, he would listen, enthralled by the practising Carnatic hobbyists in his extended family, notably The Raagam Sisters who were home-trained by their mother, Kapil’s aunt. “I have early memories of getting lost in the cyclical nature of their warm-ups, performing complex and rapid scales in unison,” he recounts.

In college, Kapil was already playing punk and math rock with a few outfits, composing personal rock ballads about his immigrant experience and the relationship with his parents, particularly as a carer for his disabled father. All of that started changing in 2011, when he caught classical guitarist Glenn Branca perform a symphony live, followed by German band Einsturzende Neubauten that played instruments built out of shrapnel from explosive warfare. These experimenters emboldened Kapil to incorporate unorthodox instrumentation (like the aquaphone) or the complexities of Carnatic styles in his music as well.

After the call-centre incident, he found himself gravitating more towards Carnatic music, using the elitist art form subversively to question caste. “It’d surprise you to know that Classical music coaches in the US and UK would gladly take on a white student but refuse to teach people from Dalit, Adivasi or Bahujan backgrounds even today,” he informs me.

Around that time, he had also begun facilitating difficult conversations about caste with his relatives and friends. For the most part they were constructive, and formative in the creation of an anti-caste artist. “I realised most UC people have two things in common– they are reluctant to acknowledge casteism exists and they are always against caste-based reservations,” Kapil tells me, reminding me immediately of the massive outrage over women protesting against Brahmanical patriarchy in 2018. His remarks were further buttressed by recent reports suggesting that most members of the South Asian diaspora believe they are anti-caste and progressive, and yet their caste identity remains important to them.

Kapil zeroes in on the issue. “The more I engaged with people on both sides of the fence, I was convinced of the need for an intersectional understanding of diasporic experiences of colourism, racism, sexism, colonialism, and casteism. The binary of oppressor/victim prevents people from looking at things from an intersectional lens and realising that you can suffer racism but still have caste privilege.”

While caste and race have many parallels, Kapil is wary of comparing them directly in his work. “I feel that tackling each requires a specific approach,” he says. A few months ago, he called out an Instagram account promoting Jat Pride, only to learn that the same user had hurled a ton of anti-black slurs and abusive messages at a BlackLivesMatter organiser. “You cannot truly be pro-BLM or anti-Asian hate if you don’t talk about caste,” Kapil adds, “because all of it - casteism, racism and colourism - are very intimately linked.”

“So when Priyanka Chopra, the erstwhile brand ambassador for Fair&Lovely, mentions George Floyd, it doesn’t really help anyone but her brand. As for me, talking about caste is the best way I can combat anti-black attitudes.”

That said, Kapil believes that there is much to learn from the best practices in anti-racist activism, that can help approach anti-caste work in the west. The clarion call to forge an international dialogue on caste rides on surging waves of polarisation and protectionism behind the efforts to quash an anti-caste law in the UK. On the flipside, we also have international and Indian labour unions uniting to restore labour rights for Dalit construction workers brought into the US (to build a temple) where they were subject to egregious abuses.

Indian diaspora, thus, needs to then open itself up to criticism, intervention and dialogue from its own members, Kapil stresses– a need that is seriously undermined by the constant flattening of brown identities into commodifiable art.

Unlike most identity-based art, Kapil’s arts practice confronts privilege and bigotry within the brown community, in tandem with his advocacy and curatorial work highlighting South Asian creatives (like fellow anti-caste artists Sarathy Korwar, leftfield songwriter Kindness, and curators like Zarina Muhammed) on DesiFuturism, a digital space he founded and imagines as an analogue to Afrofuturism. These interviews and conversations offer a glimpse into the curiosity, sincerity and thoroughness that informs his album research - a hallmark of Kapil’s process.

While he isn’t an academic or a qualitative researcher himself, Kapil is guided by a horizon of literature. Although he won’t admit it, Kapil is a voracious reader of seminal texts like Sujatha Gidla’s Ants Among Elephants, which chronicles her life as a Dalit in India and later as the first Indian woman to become an NYC subway conductor. It offered Kapil insights into the personal histories and stories that shape songs like “Glass Wig”.

Dr. Zoe Sherinian’s Tamil Folk Music as Dalit Liberation Theology was also a big influence on the record in how it illustrated the struggles of Christian Indians, an erstwhile oppressed caste that found a way back to control through conversion. The song “Exemption Hum” is heavily indebted to the hymns about their emancipation. Kapil emails me later saying, “I was fascinated by these hymns bearing western and indigenous influences… would’ve never discovered them without the CD that came with Sherinian’s book - it contained sound samples from the 70s-90s, of Dalit congregations singing these hymns.”

While he relies on academic texts for content, he turns to friends like British anti-caste artist and writer Raveeta Banger to understand the ethics of non-extractive storytelling, or how to write about women of colour, like the honour-killing victim Harpreet Kaur he eulogises in the song “Ligature Hymnal”.

With Raveeta, getting to know her over the years meant learning about her lived experiences with casteism in Birmingham which houses a heterogeneous Indian community, and learning about Dalit artists like Sumeet Samos and Ginni Mahi. Kapil was able to delineate the various insidious and subtle ways in which caste operates, that not only helped him in framing his arguments better but he was a better ally for it.

For instance, it bothers Kapil that Odisha rapper Samos, a musician he ardently admires, is compelled to take frequent social media breaks due to merciless trolling. Every time Kapil speaks up on behalf of them, or on the harassment that Sumeet and Raveeta encounter first-hand, he is acutely aware of the privilege that allows him to do so.

Visibility for Dalit activists has always been a point of major tension, as casteist hate speech continues with impunity on virtual forums. “People like Raveeta receive rape and death threats, for saying the same thing I am saying. The difference in treatment is instantly noticeable and the reasons for the same are known to us all.”

“At the end of the day, it’s not fair to expect someone who’s receiving death threats to do all the work. They deserve access to safe online spaces.”

Tying all of this with the ethical aspects of his creative process, Kapil adds, “Validation from my Ambedkarite friends, whose works lend mine its political awareness, also lend it credibility.” He explains, plotting a return to A Sacred Bore, why the record’s title track was deliberately positioned as a preamble for the rest of the record. “It’s like a disclaimer: Hello, I’m singing about caste, but I’m not a victim here and you need to know that. And it’s the first track on an anti-caste album but the album is not from an “I’m oppressed” point of view. These are my reflections on identity and privilege. And you need to know that before you hear any more music.”

Kapil is also indebted to leftfield filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, whose film Sadgati (1981) not only inspired A Sacred Bore but also helped him negotiate his position as an upper-caste man singing about caste. “It was a very visceral piece of cinema, unambiguous in its indictment of caste but more importantly, allowing people to emotionally connect with the people’s struggle. I wanted to make music that made me feel the way I did watching that film - communicating the struggles of those affected without dehumanising them with an exploitative gaze.”

That said, Kapil is still learning and constantly unlearning what allyship truly means. He remains open to criticism while holding cancel culture in great disdain. Grumbling that most leftists he knows are more concerned with gatekeeping than examining the rise of fascism, he recalls getting called out in the early days of DesiFuturism, for not probing an interviewee’s problematic caste position especially since his identity revolved around being an anti-caste artist. He unconditionally acknowledged and immediately set about fixing it.

Speaking of identity-based art by “outsiders”, Kapil also lambasts artists who exploit and profit off the suffering of others. Referring to RoundTable India’s takedown on Carnatic virtuoso TM Krishna’s unexpected turn towards activism, Kapil says, “My latest song with Lil B would have way less credibility if it was my first work, but it’s a continuation of my life’s work. My music has languished in obscurity for years before I was able to reach this level of acceptance– I needed to travel to Canada since there was no tangible demand for my music in Scotland. But I recognised an important need, personally, to talk about these issues.”

Kapil Seshasayee; Photograph: Sean Patrick Campbell

The show in Canada remains his favourite till date for more reasons than one. But it was the set he played a year before, at London’s Decolonize Festival in 2018, that was something of a watershed moment. A Sacred Bore had just come out, he had given his first big interview for the Quietus magazine, and he was finally playing to a predominantly South Asian crowd for the first time. That is when he realised how disproportionately successful “The Ballad of Bant Singh” was.

“It’s hilarious because the song was not even released as a single but I had people coming up after the set, thanking me for singing about this Dalit labour activist from Punjab. Others were asking me where they could find more information on him. That was really interesting, putting something positive like that out there. It encouraged me to keep going and keep learning,” he reflects.

A year later, the song had become even more widely popular. In Ottawa, which houses a large Sikh population, a lot of people were requesting the track before his set, which Kapil suspects is because of its pop and Punjabi folk inflections. Folk music in India is woefully neglected, he says, well into an hour of our Zoom call. Fishing out a Spongebob guitar he’d won in university “as a joke prize at a battle-of-bands”, he plays a few high notes to simulate the thumbi, a sound that is instantly recognisable to any Bhangra fan. For the song’s catchy rhythm section, he admits to transposing the thumbi sound onto an electric guitar.

“I can see why A Sacred Bore is a difficult album in some ways, which is probably why Bant Singh stood out for its accessibility. The funny thing is, me using bhangra, even for that one song, is a form of cultural appropriation. My cultural identity dictates that I keep releasing more meandering Carnatic style compositions,” he laughs adding, “At the same time, you can’t write a song about a Punjabi and not reference the Punjabi folk tradition. You almost have to reference the culture he comes from. So I went: right, I’m going to listen to loads and loads and loads of Punjabi folk music.”

“The Ballad of Bant Singh” is a fascinating case study exemplifying these subliminal aspects of Kapil’s creative process. It borrows its name from Nirupama Dutt’s book about the farmer, land rights activist and protest musician, who lost his limbs for standing up against caste-motivated injustice, a story that is documented masterfully on Delhi Sultanate’s Word Sound Power project.

With verses that ring with the cadence of Tupac, Kapil’s ballad, like the book, darts between first and third-person narratives to depict Singh’s experience and his attackers’ perspectives. “Decapitation as a token of my only love” demonstrates Kapil’s flair for elaborate metaphysical conceits, a trait he picked up from reclusive experimental artist Scott Walker. “In The Drift, Walker’s spoken-word album about fascism and post-9/11 America, he uses the motif of Elvis and his stillborn twin brother to make a statement about American mythology and hubris,” Kapil tells me.

Similarly, using the kirpan, traditionally regarded as a religious talisman conferring protection on all Sikhs, as a weapon that deprives and disenfranchises Dalits, and ultimately brings about Bant Singh’s decapitation, Kapil likens it to the beheading of Guru Tegh Bahadur. Painting a picture that is painfully reflective of the times we live in, Kapil etches a protracted lynching scene in the final couplet: “Browbeating of a man into a fine pulp/ Your absence of self isn’t something to love/ Fend off dissent regardless of cost/ Descends with each new iteration.”

“In my experience of debating the pro-caste cabal online, they are often the ones also assuming transphobic or homophobic stances. You need only look at the normalisation of such behaviour in the media they consume, to trace these dangerous roots.”

Resolute in his work around representation, Kapil continues to facilitate important conversations on social media about (mis)representation of marginalised communities in popular culture. Recently, he amplified the Eelam Tamil community’s protest against Deepa Mehta’s Funny Boy which cast non-Tamil actors in the leading roles and allowed affected Tamil pronunciations. Mehta later came under fire for questioning if it’s more important to have their story told correctly, or for it to be told at all.

“My opinion on identity-based-art is that it has this great potential to empower those who engage with it but its crude modern iterations does the opposite by truncating much-needed nuance. I feel that a lot of it stems from a basic capitalistic need to simplify every narrative into what version of it will sell best,” Kapil posits.

“I realised you have to get to people, to charm people into thinking, talking, being more curious about caste,” Kapil says before signing off, confessing that he’s finally come around to pop. His upcoming album Laal, slated for release later this year, will investigate problematic tropes in Bollywood in a more psychedelic RnB-focused fashion.

“Indian cinema is an excellent lens for exploring not only caste but a number of other issues like misogyny, nationalism, and censorship,” he says. “Tackling caste requires you to unpack subtle ways in which you or your loved ones might be continuing to perpetuate casteism: It could be casteist slurs in the songs you listen to or offensive caricatures in the Bollywood films you watch, or the Kapil Sharma show which is a cultural zeitgeist.” As the entertainment mill continues to unscrupulously deploy concerning tropes of women and queer folks, Kapil tackles these cultures in some of his upcoming singles, satirising hyper-sexualised casting in “The Item Girl” and the censorship of LGBTIA+ voices in “The Pink Mirror,” for example, while busting Islamophobic myths perpetuated by propaganda films (like Tanhaji) in the wake of a controversial Citizenship Act in “The Gharial”.

Today, his work not only adds to the continuum of diasporic ‘resistance’ artists like Asian Dub Foundation and M.I.A., but also challenges comfortable, conforming notions of caste-blind identity-based art. “My music is extremely divisive to the brown audiences who find it and come see me play. For all the folks who can relate to my anti-caste stance, there are detractors who accuse me of “self hate” and claim that caste is no longer an issue, that I’m packaging a faux-atrocity for a white audience to consume.”

“Ironically, I find it really validating that my music makes bigots uncomfortable enough that they lash out at me: clearly I’m disrupting the status quo. I’m looking forward to reading the first hit piece: I think I’ll have truly arrived as a protest musician then.”

References to Kapil’s work

1. Hill Station Reprise ft. Lil B

7. The Gharial

Prarthana Mitra is an independent writer and research consultant based in New Delhi, currently acting as outreach director for Indian Documentary Foundation. With an academic background in critical theory and creative writing, she has an extensive experience in media, policy, and development sectors where she often brings her penchant for literature and new media to ideate impact-driven campaigns. In her arts practice, Prarthana loves to explore third spaces that transgress the normative notions of gender, culture, class, and discipline, recently developing an interactive hypertext fiction on the migrant workers’ crisis. She also spends a lot of time thinking about the subversive power of female body hair and how poverty intersects with mental health. Her papers, essays, interviews, and short stories have appeared in WILD CITY, A Humming Heart, Participatory Research in Asia, The Indian Economist, Cult Critic Film Magazine, Doing The Rondo, and How 2 B Bad zine.