Two Voices of Dissent from Gujarati Dalit Poetry/ Heer Nimavat/ Issue 13

Curated and translated from the Gujarati by Heer Nimavat

Editorial note:

This is not an essay, but a work of curation. It contains a brief introduction of the poets, translations of four poems from Gujarati, and a brief translator’s note.

Translator’s note:

Amidst the highly under-theorised and under-translated literary world of the Gujarati language, ebbs and flows of socio-political and cultural undercurrents have extended to it an occasional limelight. The Dalit Panther movement, the Bhakti movement, the 2002 Godhra riots, as well as autobiographical narratives of the independence struggle and the National Emergency (most popularly written by early RSS activists), translated knowledge of Gujarati literature has been an ironic and fascinating blend of reverence and revolution.

One finds in Jayant Parmar and Neerav Patel’s works, a haven of Limbale’s poetic aesthetics (Towards an Aesthetic of Dalit Literature, Sharankumar Limbale, Orient Longman, 2012). The poetic translatability of Parmar’s descriptive metaphors is not short of pleasurable to a translator. The imagery, while deeply rooted in the Indian context, finds a satisfying equivalent in its English moulds. While ‘A Dalit Poet’s Will’ eloquently questions the very concept of ownership and its denial to those rendered subaltern, ‘I Have Witnessed Words’ seems to excavate anew compartments of human language from the pained perspective of a Dalit.

One may locate Neerav Patel on the polar end of his contemporary’s stylistic approach. Abandoning verbose metaphors for a succinct poeticism, he makes use of popular references and a realistic tonality to evoke Dalit voices armed with satire. ‘We the Ultra-Fashionable Folks’ brings to the forefront a class-caste conflict which finds itself in the clutches of confusion before the deluding and mobilizing nature of fashion. ‘The Old Woman and I’ inhabits a contrary rural voice, laying bare the hopeless plight of a Dalit—who is disadvantaged in both, social and economic realms—in feeble conflict with a cyclically parasitic political system (lovingly called democracy). The language of the poem is heavily dialectic, most commonly located in the Mehsana region in Central Gujarat. The use of a direct style of storytelling in combination with a distinctive narrative voice prove to be a challenge for a translator (albeit delightful).

*

Jayant Parmar (born October 11, 1954) is an Indian poet known for raising Dalit issues in his poetry. Parmar was born in a poor family. At a young age, he began to paint miniature paintings for a frame maker. Parmar realized that the frame maker had a separate pot for him because he was Dalit. This led to him quitting.

Parmar taught himself Urdu from a language learning guide at age 30 after he developed an appreciation for Urdu poetry while living in a Muslim-dominated area in the walled city area of Ahmedabad. He has published a number of poetry collections: Aur (1998), Pencil Aur Doosri Nazmein (2006), Manind (2008), Antaral (2010) and Giacometti ke sapne (2016). Parmar won the 2008 Sahitya Akademi Award in Urdu for Pencil Aur Doosri Nazmein. His work has been translated into Kashmiri, Punjabi, Hindi, Marathi, Bangla, Kannada, Gujarati, Oriya and Slovenian.

Amidst the poet’s widely theorised and cited works of Urdu, his Gujarati poetry (while slimmer in volume) has received a Nelson’s eye owing to its under-representation and under-theorisation in Dalit studies and the greater planes of Indian literature.

A Dalit Poet’s Will/ Jayant Parmar

What all does a Dalit poet bequeath after himself—

Paper grimy with blood

On the night’s temple an ebony moon

An ocean of inferno on a pen’s nib

An ancestral spark set ablaze in bloodlines

He doesn’t orchestrate an attack on you

Of metaphors

Of similes

Of individuality

Burden loaded on a mule’s back is he

In himself an injured umbra

He has no existence

No contrast between him and a broken cup

Painter of dung and mud panoramas

He possesses at least that understanding

In an hourglass, in the scent of refugee sand

In the sunflower of rebellion

On a penpoint, in the inkwell’s charcoal sap

The craft is safe and sound

But now in search for its essence

Identifies oneself with immense pride—

Dalit!

I Have Witnessed Words/ Jayant Parmar

I have spotted words in rain

Slipping into a hessian sack

In a queue of kerosene

Crumpled in the orbs of dejected children

I have encountered words

By a buffalo’s corpse

Standing pot-in-hand, with an empty stomach

Slurping chai from a cracked cup

I have seen words at the temple

In the heart of an innocent goddess

In bloody tears wailingly shed

In a whip’s cry on a back

I have regarded words

Renouncing self from self

Loathing itself

I have witnessed words.

*

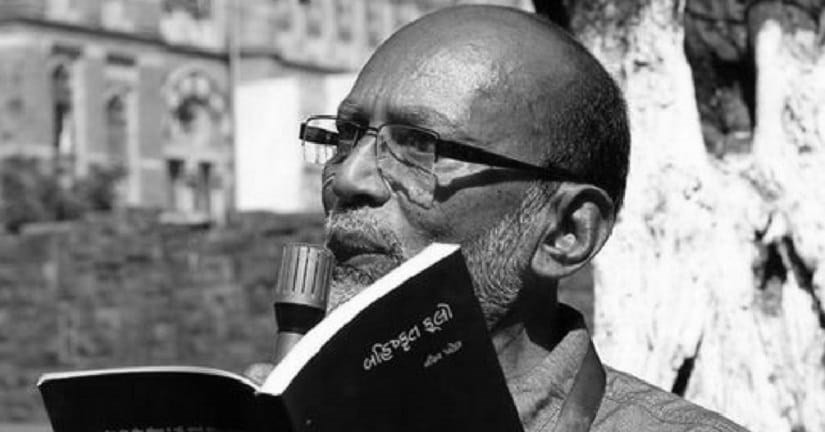

Neerav Patel (1950-2019) was born in a village in Ahmedabad. He changed his birth name to Neerav Patel because he faced atrocities due to casteism. He pioneered the movement of Gujarati Dalit literature, publishing the first ever Gujarati Dalit literary magazine Akrosh in 1978 under the auspices of the Dalit Panther of Gujarat. Short-lived little magazines edited by him or with others (namely Kalo Suraj, Sarvanam, Swaman and Vacha) and organizations (namely Swaman: Foundation for Dalit Literature and Gujarati Dalit Sahitya Pratishthan) founded by him with other writers were instrumental in boosting the movement. Burning from Both Ends (1980), What did I do to be so Black and Blue (1987), Bahishkrit Phulo: Gujarati Dalit Kavita (2006) and Severed Tongue Speaks Out (2014) are some of his works on Dalit poetry in English and Gujarati.

He received the Mahendra Bhagat Prize (2004–2005) from Gujarati Sahitya Parishad, and the Sant Kabir Dalit Sahitya Award (2005) from the Government of Gujarat. He passed away in 2019 battling cancer.

We the Ultra-Fashionable Folks/ Neerav Patel

We are members of a foppish clan

Our ancestors used to adorn

Tripple-sleeved shirts

Their ancestors’ ancestors

Used to swaddle their form in just the shroud

Their ancestors’ ancestors’ ancestors

Used to roam around in sole skin

I myself am no less foppish

Was meandering along the footpath across the C.G. Road showroom

And bestowed upon by sir, collarless sleeveless—

A vest

So, alike Salman Khan I am cruising around with my chest out

And like Sanjay Dutt, I am ballyhooing my biceps to the savarnas

Ah! The upper-caste younglings are getting impatient

To catch a glimpse of the label on my garments

Poor things ...

How come to accomplish such recognition

Without caressing my untouchable nape

“Oh! It’s an odd-sized Peter England!”

Indeed, we are members of a foppish clan

The Old Woman and I/ Neerav Patel

1.

Humph! You have been frauding for 40-50 years

But their business has had no fruition

Not two-five years have passed

And here they are, appealing for votes!

Understanding escapes me,

Where the hell are all these votes going?

They’re saying that Vaalo Naameri is standing

Popular opinion goes that he’s a good fellow

It’s being said that since Babasaheb’s times

He’s been working for the benefit of the poor

Speak old woman, what do you wish to do?

You are naive by birth, the old—

Grinding labour and gobbling it up

I hear fire birch is being distributed per head?

And a 100gm packet of gathiya snacks

A car to carry and drop off

Live out old age for a couple moments

Drink a sack full of water if you feel like it

May God do good to Vaala Naameri

But the vote will go to brother Manu

Go, go ahead and bargain

Tell them, there’s two—

The old woman and I

2.

Brother, I’ve heard that they are offering 10 per head

If you wish to hand us twelve

There’s two of us—

The old woman and I

They’re not much

Two days worth of meagre wage

To us, two moments of rest from toil

Otherwise, we go to bag bones

Mago Metar is patroning five for each sack

Otherwise, if we have bread by sundown

Hunky dory.

Here brother, we bequeath our governance and wealth to you

To us, only our struggle suits

The sun is atop

Time runs on the old woman

We are to sin

But we are to keep our words

The vote, surely submitted to Manubhai

Tell me, want to give twelve per head?

There’s two of us—

The old woman and I

Heer Nimavat is a third-year BA Honours English student at Miranda House College, translating between Gujarati and English. An alumna of the Mitacs Globalink Research Internship, she has been translating and conducting linguistic research on Medieval manuscripts discovered in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat at the University of Toronto. She is the only translator to have worked on Gujarati at the prestigious university. Currently working on her first full-length translation project, she has also received a Sahitya Akademi research and translation grant to work on indigenous oral literature in Gujarat.