Carnet de Tangier/ Jigar Brahmbhatt/ Issue 12

I was carrying a diary I had purchased in 2010 from a roadside bookseller in Pondicherry. At that time, in an insufferable state, all I cared about was getting my hands on cheap blank pages to record my effusions, and the seller had thrown in the diary for peanuts on purchase of few books. It was many years later, finding it buried deep in my stuff during a rare round of cleaning, when it had struck me that it was quite an elegant diary. Carnet de Tangier was written in the middle, and it was explained in French and Arabic on the yolk-colored cover jacket that the diary was part of a special edition by Librairie des Colonnes, a bookstore in Tangier. Samuel Beckett had been there, per google, as had many literary luminaries. I asked the cabbie to take me there first. Putting my rucksack down, I showed the diary to a man on the counter. “Yes this is us! You found it in India?” He was pleasantly surprised. Someone must have purchased it from here, brought it to Pondicherry, and somehow left it unused. One of chance’s wonderful mysteries. “Good of you to hold onto it!” the man beamed.

I browsed the collection in the bookstore for a bit and left for the Kasbah. I was finally in Tangier inspired by nothing more than whimsy.

Ibn Battuta caught my attention the moment I stepped out of the cab, the name gleaming over a citadel-like structure at the end of the street. The old cabbie threw hasty instructions in Spanish and drove off. Before I could make sense of my new surroundings, a local boy started getting friendly. I pulled out my phone to consult google maps. The boy kept insisting that he could help. I was half talking, half googling. He got me to mention the name of my guesthouse and disappeared from the range of my vision. Google showed that it would take seven minutes to walk down a sloping passage until a nearby node from where an uphill right should lead straight to the guesthouse. I began to do just that when the boy whistled from some distance, “this way.”

He was on a narrow passage on my left that went deeper into the Kasbah. I raised my phone-bearing hand and said, “I am good, thank you.”

“Kasbah confuse you,” the boy shouted, “Google don’t know Kasbah.”

I ignored and started walking down the slope when a suited souvenir seller, standing amidst his goods in a kiosk, insisted with the cold authority of a mafia henchman one sees in movies, “boy show you way.”

He made his surprising involvement appear as natural as the cold wind that blew that day.

The boy came running, “this not good way. I born here. You trust google but not one who born here?” I waved it off and resumed walking, but he was really after me, “Where you from? Where you from?”

“India.”

“Ah, Shaaruk Khan, Amita Bacchaan…”

“Listen, how much time your way?” I asked.

“Ten minutes brother.”

“It takes seven minutes this way.”

“I say ten meaning short way. Ten not mean ten. I say by feeling, not like google, exact, exact. Come, come brother.” As if that wasn’t enough, the souvenir seller, already eager to convince me, solemnly advised, “No single way to travel in Kasbah. Boy show you best way.” The boy made a “let’s go” gesture. He was not going to give up. Being swindled was an easier option.

Made to walk a maze of alleys hemmed in by shops and houses, we reached an arched gate in the exterior Kasbah wall that opens to a sudden, unexpectedly breathtaking view of the Atlantic. I stopped to admire the view but the boy was racing, so I had to take an immediate left along the parapet towards the extreme end of the cliff. We had been walking for more than ten minutes and there was no guesthouse in sight yet. By no means was it a short way or the “best” way. “Little bit more,” the boy kept saying all along. But I had no complains because the scene I found myself in had completely captivated me.

When we reached the guesthouse the boy triumphantly declared, “what I say brother? I show you way.” He rang the doorbell for me but did not leave.

“How many languages do you know?” I asked.

“Arabic, Spanish, French,” came a swift response. “English,” he added a moment later and laughed.

When the door opened and I was about to step in, he asked, “What? no gift!?” I had already felt my pocket for 20 dirhams but deliberately acted bemused. “I help! Now you give token,” the boy demanded.

“Why?” I asked in all seriousness. He was not prepared for it and his eyes went wide. Down below near the beach a car kept honking.

Then something urgent occurred to him. “Parvi Babi,” he blurted out. I couldn’t help let out a hearty laugh. Mention of Indian celebrities was the only way he knew to establish trust with me. I handed over the money and asked, “How do you know these names?”

His face lit up. “My father he love Indian film… he watch in Cinema Rif when he young man.”

Once seen, the boy’s skinny arms were difficult to unsee and colored my idea of him. I imagined him struggling to be attentive while an eager father was making him learn about Bollywood. “I show you way” has been a means through which many in Morocco have made quick buck over the years, the country’s medinas being famously maze-like, and the boy’s contempt for Google must be for ruining these earnings. He had a sharp face and wore a big cap that looked odd on him. “What you gonna do with the money, buy more caps?” I asked. My little joke was missed on him and he kept smiling with an open mouth. Then to allow a fitting closure he said, “Shami Kapu… Raj Kapu…” and ran away.

Only when I had checked in and was looking out of the window of my room towards the harbor did I recall how awestruck I had become when the cab had left the thoroughfare, opening my vision to a wide sweep of the sparkling beach and the hilltop medina on the extreme left with all the white houses, in one of which I now stood. The immediacy of the sight had made me think of it as a rustic Santorini for lack of a better comparison, and the transience of looking from a moving cab had left me wanting. On top of that, I was unprepared for the guesthouse, which surprisingly turned out to be a well-curated mansion, so when a caretaker named Issah walked me through corridors filled with books and curiosities from around the world, I understood that a lot was to be unpacked, not to forget all the newness hiding in the dove-colored alleys of the medina that housed the Kasbah. It was overwhelming for the senses as happens in a new land. What helped was a refreshing cup of mint tea with which Isaah welcomed me, artfully served keeping to the tradition.

In the train from Fez, I had been reading The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles, the quintessential Tangier expat who wrote disturbing stories about romantics seeking purpose in strange lands only to end up in disaster. The sequence I had read described a wandering American being led by a friendly but persuasive Arab out of a Kasbah and downhill to an open land in total darkness where, persuaded further inside a shabby tent, the American was to encounter something at once alluring and sinister. He could sense the Arab being evasive and could easily run away, however Bowles writes, “The combined even rhythm of their feet on the stones was too powerful.” The little Arab I had encountered was also persuasive, but the danger of the Tangier of 1940s, a lawless zone where spies, hustlers, bohemians, authors, and all sorts of outsiders sought refuge, described by Jean Genet as “the very symbol of treason” in The Thief’s Journal, was already subjected to time’s eraser. It is now a mellow place.

Later after having rested a little, I asked, “How is café Hafa to grab a bite?”

With a crew cut and the physique to go with it, Isaah could stand in for Cuba Gooding Jr. in Men of Honor and you won’t even notice. Soft spoken and suave, he sat in the reception room behind a desk on which was audaciously placed, apart from the stationery, a beautiful bird. In fact, calling it beautiful would be an understatement. It was hard not to keep staring.

“Chinese golden pheasant,” Isaah said.

“Yours?”

“Oh no, taxidermy not my thing. Belongs to the owner,” he said and in the same breath added, “That place is good for tea but you will hardly get any food there. Try Petit Socco instead. Many eateries.”

Out on the streets again, with no rucksack on my back, it was easy for me not to draw unnecessary attention. All I had to do was walk as if I knew where I was going. Young men in groups were to be found around corners, and not all of them could be self-proclaimed guides, but it was in my favor not to appear like a walking wallet in their midst. Hans Christian Anderson, arriving in the early 1860s by the sea, describes a confrontation in a book titled In Spain and a Visit to Portugal: “The steamer stopped pretty far out, and cast anchor; and two or three boats with half-naked, sunburnt Moors came running out to us; screaming and making signs, they ascended the side of the steamer.” Sunburnt indeed but the Moroccan men I saw were usually smartly dressed, slim-fit pants and trendy jackets being popular choices. French was not just an adopted language in these parts; looked like they also kept a tab on French fashion.

I saw swarms of them in café Hafa, which is like an amphitheater with the Strait of Gibraltar as a stage. Descending terraces populated with stone tables and cheap plastic chairs, a sitting arrangement that has not changed since a broken-hearted young man named Larbi Layachi, sent to prison at being mistaken for a smuggler while innocently fishing, convinced Paul Bowles that he had a life story to tell. Larbi’s spoken stories needed a patient ear and lots of kif. They must have sat in the café recording the stories directly in English. Because imagination has no shackles, it would not be far-fetched for them to find William Burroughs sitting few tables across, masticating for his hashish-induced ramblings the term “naked lunch” just suggested by Jack Kerouac, whose recent publication of On the Road must have provided him with fiscal means to visit his friend; and there would be no surprise if each party nodded at the other from time to time while, standing close by, a bored Truman Capote looked on, sometimes at them, and sometimes at the vagueness where the Mediterranean and the Atlantic became one, not sure yet that he was forever conceiving In Cold Blood.

I was aware it would be a ghostly place now, and I did not expect to understand by going there, more than I already did, the makings of literature. Café Hafa was extremely cold on that windy day. It was difficult to find a table, and as I climbed up and down the terraces to look for one, I had attracted attention. Young people in stylish hoods entered and left with the cool confidence of walking on known turf; they bumped fists, huddled around their tables to smoke, joke and laugh, and at times appeared lost while looking at the endless spread of water. Some of them had singled out a clumsy me going up and down as an object of wonder. I paused at a corner of the topmost terrace to take a proper look, and found someone sitting down below waving at me.

The man was happy to share his table. He asked whether I was from India and left it at that. I found out that he was from Chefchaouen, had worked in an oilrig long back and was now living alone in the city. He soon got busy brooding over the concerns that must have brought him there. No waiter had appeared until then. I looked for one in vain. The café looked terribly unkempt. Had it not been for the stories of its once-renowned literary clientele, there was no magic here; like an empty stage after the drama has played out. The sea breeze directly bit into my nose. I covered it with the muffler and shoved my hands into the jacket pockets. “On a clear day you can see the mountains of Andalusia,” the man said and came right to the point, “Want hashish?” Surprised, I shook my head. He shrugged. Then a waiter did appear with a big rack of mint-laden glasses.

Like any café in North Africa, mint tea is why you come here. A hot sticky syrupy glass of mint tea allows you to sit for hours. No wonder the café is unkempt because how much profit can be made on tea alone! A distant uncle who had migrated to Bombay for work in the 50s had shattered my romance about the Parsi cafés during a conversation. I always wondered that in a slow time like that compared to our post-smartphone age, it must have been lovely to sit with a cup of irani chai and read until one’s heart was full. However, the uncle was quick to point out that the owner would not allow you to sit a minute more after the tea was over! And rightly so, because he had a queue of customers to serve. Café Hafa has always been a place where you would want to sit and work on a novel. What it preserves is a bygone sluggishness locals seem to value. I relished the scene until the tea lasted and left.

For hours, I wandered in a surrealist pleasantness that comes about by not knowing where you exactly are. Rows of whitewashed houses going uphill and downhill on whim, narrow forking alleys with its ancient shops, lush parks appearing new on repassing, and antique lampposts jarring my constantly-forming idea of the place. Everything save the trees and the earth was a seductive white. I paused to admire an unused palace, a Carthaginian tomb, a house over whose wall a sprawling fig tree was visible, an old hospital that could pass off as a quaint cathedral, and countless views of what could be either the Atlantic or the Mediterranean, Tangier being at the choke point of both. I had at my disposal the oldest recreation known to man: slow walking. The illusion I got during my long undertaking was that of being in a Spanish village, and my memory of it only being a literary one, I expected a boy named Santiago or a Sancho Panza to pass by, but I instead met a Toufik and a Yousef.

Toufik runs a stall near Petit Socco (Spanish for souk, or market), selling, among the regular kebabs, a potato fritter that appeased my Indian palate. He stuffed couple of them in a hollow Berber bread and made an on-the-go meal for me by adding condiments that were a tad bit sour for my taste. I washed it down with pomegranate juice and tried to have Toufik tell me everything about this cousin of vada pav. The mustached man could only say, “I make, I make.” Was this lone snack a result of some past interaction between the two cultures? Toufik had not even cared to name it anything. He called it “batata” and chuckled. I tried to remember how potato had reached India via the Portuguese sailors. Did they also make a stop here in Tangier? Thinking that nothing in life could be that simple, I focused on the archaic charm Petit Socco had retained and stood there for a long time taking in the unhurried busyness of the place. The name of Toufik’s shop was “Layachi”. I was sure there was no relation with the erstwhile writer, but the fact must have made me stop at his shop and no other.

Going downhill from the café-cluttered square of the Socco to Gran Teatro Cervantes, a century-old theater dedicated to Miguel De Cervantes that was sadly closed for renovation, back again to the square and upwards to one of the solitary alleys, I had tired myself and stood recovering at Yousef’s bookshop. Along with Mohamed Choukri’s For Bread Alone and Tahar Ben Jelloun’s The Sand Child, I also purchased a postcard of an older Kasbah.

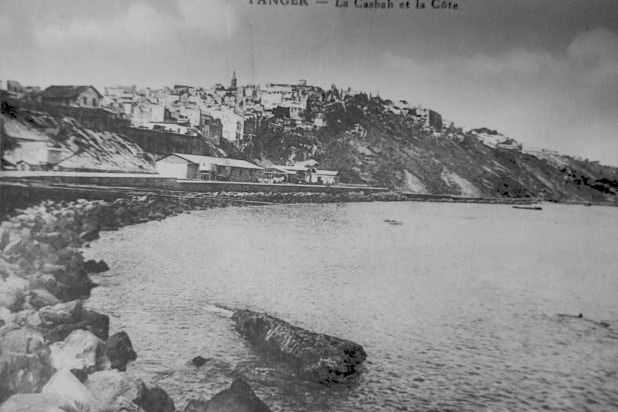

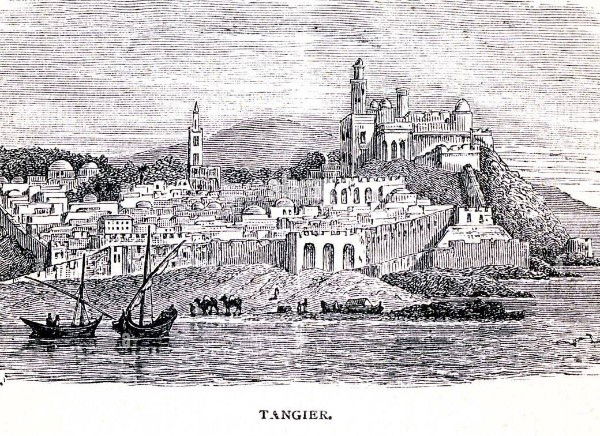

This is what Hans Christian Anderson must have seen on arrival, I thought. He describes “a train of heavily laden camels” over “yellow sand of the desert behind the town”. I was aware of Tangier being a unique port, with water on one side and the Saharan wilderness on the other, but there was no hint of any desert from what I had encountered so far; or maybe continuous settlement over a century had blocked for me what the creator of The Little Match Girl could easily see. How alluring that a city forever sheds its pasts that then lives on in faulty memories and fading photographs!

Yousef quoted 30 dirhams for the postcard, but we settled on 20. The only thing that kept him from being mistaken as a Parsi was the Moroccan hat. His easy, loose dressing, very reminiscent of the bawas, hinted that he lived at the back of his shop. “Do you have etchings or lithographs?” I asked.

He squinted and wordlessly rummaged through large wooden drawers.

“On the way here I saw some pillars,” I said. “By the street side… they were just there supporting nothing.”

“Romans,” Yousef said without looking at me.

Few months ago in Rome, dazzled as any newcomer would on witnessing the glorious Pantheon, Julius Caesar’s grave, House of the Vestal Virgins, Caligula’s Palace, that famous fountain from the movie La Dolce Vita, my initial awe had, after few days, turned into a strange fatigue. While everything was a treat for the senses, the mind had come to expect that any sight was soon to be outshined by another; with the city being readily served on a platter, a sense of discovery had died. But here in a costal town in Africa, opposite a playground in which football was being played with renewed vigor after a recent win during the FIFA World Cup, to encounter these pillars by the roadside, ignored as if they were abandoned kiosks, was like momentarily stepping outside time. Their out-of-place-ness made me wonder more about Romans than my visit to Rome ever did. What “is”, I wondered, is always a result of many overlaps.

“Are the pillars part of some larger monument that existed once?” I asked.

“Can’t tell. They been around for ages.” He lifted his head, “Must have been placed right after the time of the Carthaginians, come to think of it.”

“It’s truly surprising that they were here too. I saw the tomb.”

“Oh Tangier has had outsiders taking over since forever. French and Spanish were the last to fight over us, even English wanted control.”

“What was so special?”

“Location I guess. It was a gateway to Africa for them.”

“And Arabs?”

“They are integral. They have been around longer. The king is Arab.”

“Were not Berbers the original settlers?”

“That was at least a thousand years ago before the Arabs conquered them. Now we are all one people. Berber, Arab, or a nostalgic expat who has stayed back. Doesn’t make any difference.”

I considered it, and he carefully placed a gorgeous etching on the counter.

“Do you have anything older, like from the time of Battuta?” I asked.

Yousef mused for a moment. “Were there etchers that far back? I wouldn’t know. This here is by a Baroness. I would say… 18th perhaps 17th century.”

He kept his gaze at the engraving some more and said, “him… he was Berber.”

“Ibn Battuta?” “Yes.”

I had had lunch with a Berber family in Ourika valley a week prior, and while I loved their local produce, especially the argon butter, their nomadic past was not very clear to me. I knew the Atlas Mountains have been their home, but did not expect them to be seafaring. I asked the same to Yousef, who responded, “Oh but they were everywhere, in Tunisia and Algeria, also in Egypt. They were the pre-Arabic inhabitants of all of North Africa.”

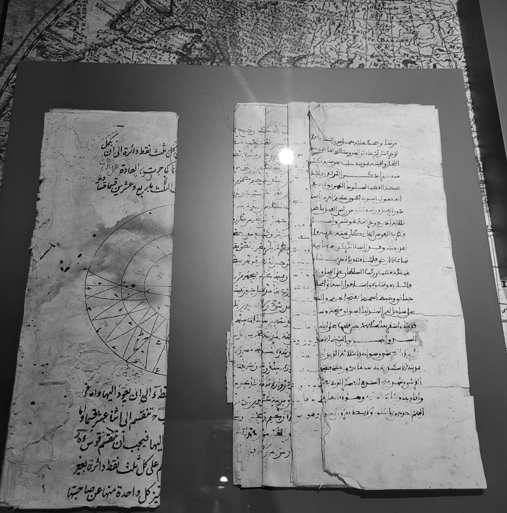

“My departure from Tangier, my birthplace, took place on Thursday the second of the month of God, Rajab the Unique, in the year seven hundred and twenty-five”. So begins the first chapter of a book with a curious title: A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling, popularly known as Rihlah or The Travels of Ibn Battuta. In 1325, a young Battuta left home for a short pilgrimage to Mecca on a mule, but his travelling went on for 29 years covering the equivalent of 44 modern countries in the then Islamic world, journeys that were later recounted to a juror named Ibn Juzayy by the traveler finally returning to Tangier as an old man. Having spent many years in Delhi and elsewhere in India, Ibn Battuta had also visited a coastal town in Gujarat called Khambhat. This fact was very interesting to my grandfather, who as a teenager in the Khambhat of early 1950s, whiling away a harsh afternoon in the coolness of a local library, had chanced upon it in a Gujarati history primer.

Married at 17, grandfather moved to Vidhyanagar to study further and raise a family. By the time I finished my graduation in 2006, he had forgotten most of the history he had read while acquiring his bachelor’s degree. He had worked as a salesman all his life, and the wear and tear that happens to unused information had for him happened. Constantly occupied with the thoughts of making ends meet, he did not have the luxury to be curious about the world. While in the Sowcarpet area of Chennai for business, he used to stay in a lodge named Vasant Vihar, always in the same room with a small balcony facing the Mint Street. It so happened that after moving to Chennai for my first job, I also stayed in the same room for three years. All alone in a new city, I drew a strange kind of comfort from that room; and even though grandfather had stopped working towards the end of his life, he continued to visit Chennai once every year, to catch up with old acquaintances and to have a sojourn with his grandson.

During one such trip of his to Chennai in 2007, I had showed him a translated copy of Rihlah, purchased at a discounted rate from Landmark bookstore. A lonely neuron, waiting for decades in the recesses of his mind, had fired with such intensity that the effect could be instantly felt in grandfather’s wide wrinkled smile. “Yes, Ibn Battuta! He came to Khambhat!”

I understood that for my grandfather, it did not matter who this Tangerine traveler was and how his life had played out, but that centuries ago, someone had visited the place of his birth. The Khambhat of today is desolate compared to it being “one of the finest there is in regard to the excellence of its construction” as per the traveler, who refers to the port by “the arm of the sea” as Kinbayah. It had amused grandfather no end because it sounded better than what the British had done by calling it Cambay. In Tim Mackintosh Smith’s edited version that I own, the traveler describes being invited to a banquet by the governor of Khambhat and by an amusing chance, a local qadi and a sharif from Baghdad sat facing each other, one blind in the left eye while the other in the right. The sharif, treated by all with veneration, insulted the qadi for being half-blind. The governor laughed, ignoring a similar lack in the speaker. The qadi who could not retaliate, Ibn Battuta observes, was put to shame.

Sadly, the book did not have more on Khambhat. For instance, grandfather wanted to know, what grew in the gardens? How were the houses of common-folk like? Did they also make sutarfeni, his favorite sweet, back then? How did they manage sewage? What jokes could a Baniya broker share with an Armenian merchant? I had taken a printout of a lithograph for him, posted by a maritime foundation doing research on the trade routes of Gujarat in the 16th century, but nothing, not even the lovingly etched glimpse of the long-lost port quenched his childhood wish: to see for himself what Ibn Battuta had seen.

After looking at a few original dull-brown pages of Rihlah in an exhibition center, the same citadel-like structure I had noticed first thing on coming out of the cab, I kept thinking about that modest room in a distant lodge where I had read the Kinbayah passage to my grandfather. I remember him musing over the kind of place “this Tangier” would be. Ibn Battuta was not his only pointer to the curiously named city. Sometime in his life, he had run into a Sindhi man who owned an electronics shop in Tangier. Much about this encounter was forgotten (was it in a train or in a merchant friend’s shop?) except the man’s surname: Dassani. “I think he was with me in a train,” grandfather would say only to shake his head and change the locale. Over glasses of almond milk sold by the Kakada Ramprasad sweet shop in Sowcarpet, we had mused about the circumstances that could have led Dassani that far. To us looking from a humble lodge, Tangier was a preposterous impossibility. A place you can spend your whole life knowing without, a place where only some Dassani would go.

I went through the rest of the Ibn Battuta archives with a disturbed disposition, suddenly overwhelmed by the fact of being there, unable to focus on the currency and clothing of the period, mindlessly starring at a dagger on display that a man in medieval times had to carry; and later, after tracking down a tomb where the famous traveler was possibly resting, it was as if not only the Kasbah or the city at large but everything had turned gloomy. An unbearable urge to call my grandfather got hold of me. “Guess what dada! I am in Tangier!” I wondered how he would react to that and failed to stifle an outburst. Unable to go back to not missing him, I wandered some more and stood near the arched Kasbah gate admiring the vastness of the harbor until sundown.

For the rest of the night, the wondrous mansion I was staying in kept me distracted. In a 1961 essay titled The Ball at Sidi Hosni, Paul Bowles describes being invited to a house party thrown by a rich woman at Derb Sidi Hosni in the Kasbah, in which he observes: “inside are some two hundred people amusing themselves, but the house is so designed that there are surprisingly few people at any one spot.” It could easily apply for my temporary dwelling as well. Not that the mansion was huge but it was “so designed,” the corridors connecting many differently sized rooms were narrow and gave one an illusion of traversing a labyrinth. It took me a while to feel my way around with confidence. Even the minutest of space, be it a remote corner, was utilized. The entire place was bursting with furniture, hangings, and bibelots from around the world; the lounge draped in Moroccan and Turkish fabrics had a library with the choicest of selections. The patios with its vegetation and decorated balconies facing the sea added to the charm. It was a huge cabinet of curiosities; a kind of living space the mad imagination of a compulsive ethnologist could conjure up.

When Isaah told me that the owner was a Frenchman, I was not surprised. For an expat to buy a house in Tangier and refurbish it has been so common it has become a cliché; but seldom could one find a space so lovingly curated. What surprised me was the fact that the owner himself did not live here. He lived in a small, stark house farther downhill from Petit Socco, far removed from the exuberance of the mansion. “Why so?” I asked.

“I do not know. He is very taciturn,” Isaah said.

“Tell me what you know.”

“Well, there is not much. He bought the mansion in the 70s. Lived here until few years back when he decided to turn it into a guesthouse. That’s when I was brought in as a fulltime caretaker. Everything you see in here is assembled by him, collected during his travels.”

“Is there a theme running across each room? A map of Mansa Musa’s empire on one wall, next to that of a portrait of the maharaja of Jodhpur, cabalistic renderings on another wall. A lot is going on here.”

“All I know is that he is old Mr. Gustav who lives with a poodle, who happens to visit every few days to see if the place is in order,” Isaah said.

“But surely in all these years you would have found more about the man, about his choices in assembling only these artefacts and not any other?”

“He keeps to himself.”

I was borderline annoyed by Isaah. He was either deliberately trying to make Mr. Gustav mysterious, or was happily uncurious. He pointed my attention to a framed photograph on the coffee table in the lounge, of the owner as a young man, reclining on the same couch on which I now sat. But there was no trace of the present-day décor in the photograph. Even the cushioning on the couch was different. Draped in a thawb, Mr. Gustav gave a faint smile but appeared as though he was about to burst out laughing. There seemed genuine affection in his eyes for whoever was taking the picture, his demeanor happy. Something about it had affected me but I was not able to put my finger on it. Giving a good stretch to my legs, I relaxed into the cozy couch, and skimmed through gorgeous hardcovers on Moroccan history and culture while indulging in a delicious chocolate pudding, which as per Isaah was a house specialty.

Later that night, I found more photographs in a wooden trunk in the guestroom assigned to me. The trunk lay in one corner like mere decoration, a flowerpot resting on top of it. All it took was a desire to see what was inside. Young Mr. Gustav came across as a community man in these old photographs, pictured with other young people, all appearing either to be in the middle of happy discussions or simply having fun, their faces animated with eagerness and pride, as if part of a clique. Europeans all who had found respite in a faraway country, their acquired dressing reflecting the inquisitiveness that must have bounded them all. There was a woman too Mr. Gustav seemed to be fond of: him holding her from behind on a beach, them casually kissing under the arched Kasbah gate, the more I looked the more I felt like learning yet more about him. It was not a regular guesthouse providing mere bedding and breakfast. It was a museum of a life lived at the fringes of the ordinary, and although I was only approximating, I started wondering, with my head resting on two fluffy pillows and my eyes fixed at the dark outside the window from where thick Tangerine air rushed in, whether it was even in my design to live with such lightness?

For days afterwards, I spent most of the sunlit hours in the mansion, lazing on the couch, reading Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus without any intent to finish it; or on the terrace with its swimming pool overlooking the harbor, enjoying a pint now and then, retiring to my room only for a nap. Isaah usually minded his business, and the only other guests were a Swedish couple who were always out. I loved walking through the corridors without bumping into another soul and took long pauses to admire the walls and bibelots, trying to figure the stories behind each article. I was content to find myself in such a space, because it looked like an outlandish fulfillment of an adolescent yearning.

Despite growing up in a joint family, it was not much of a struggle in the house to find a quiet corner to dream, but I used to wish, very strongly, to retire to a space all my own. I was not able to understand the meaning of that wish, and because it was inarticulable, it remained passive. But at different turns in my life, I have had a vague glimpse of the possibilities it suggested. The image that comes to mind is Mario jumping towards the flagpole, which marked the completion of a round in the Mario Bros. video game. In the limited vision of my childhood, I saw it as a bizarre but complete world in itself. I was desperate to know what lay beyond the flagpole, because no matter how much I tried I could not make Mario jump over it. Then a cousin gifted me one of those “9999 games in 1” cartridges in which there was a tempered version of the game that allowed high jumps. Thoroughly excited, I made Mario jump past the flagpole and never released the run key, my eyes glued to the TV, but the pixelated red-bricked background repeated ad infinitum, taking me nowhere.

Like my curiosity to know what was beyond the flagpole, my adolescent yearning was also for something beyond my immediate reality. Over the years, moving away from my family to new cities, and thereby moving farther and farther away from their idea of the way things should be, I have been confronted with biting solitudes, which, apart from being scary at times, have inspired purposeless movements through stranger streets. A portion of the world thus, walk after walk, has gathered on my person like soot and dust and moisture, and it is only in the stasis of the many solitary rooms I have lived in that it has mixed into my ever-forming idea of the way things are. I have read a lot in these rooms, never sure of what I am really looking for, and the yearning continues to live inside me, forever unfulfilled, often dormant, but always looking out. Grandfather had spent a quarter of his life in trains, but his circumambulatory movements, different let’s say from that of Mr. Gustav’s, never really took him beyond the bounds of the known. He had brought his family to Vidhyanagar from Khambhat, but neither he nor my father were interested in making another jump. My own temperament, being part of the same lot, is not that of a traveler. Migrating from one city to another for work, I am always missing home, always struggling against the dichotomy of stasis versus movement. That is why, being in Mr. Gustav’s faraway mansion, I discovered an uncanny familiarity with the space, as if I had glimpsed the other side of Mario’s flagpole.

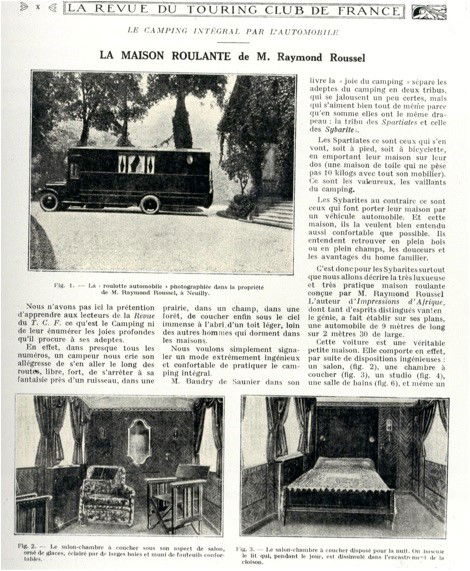

Had I been as creatively daring as Raymond Roussel, I would have achieved a perfect amalgamation of stasis and movement, a “mansion on wheels,” which he actually built for himself in 1926, a van equipped with electricity, a saloon, a bathroom, a study, even servant quarters. He had driven it to Rome and showed it to Mussolini, who as per Roussel was impressed. He also had an audience with Pope Pius XI who showed a keen interest in seeing the van, but Roussel was not allowed to drive it into the Vatican. Ten meters long, people said it looked like a hearse, but he had a luxury of halting the van whenever an idea struck, to use the portable study to work on his fanciful narratives, before resuming the journey until another pause materialized. Lacking the spirit of crazy passionate men who have decentered their homes, I used the temporary lightness of being in Mr. Gustav’s mansion to organize these scattered thoughts, putting them down in Carnet de Tangier, which fatefully translates as Tangier Notebook.

One evening, after having my heart’s fill of the view of the harbor from the arched Kasbah gate, as had become my daily ritual, I went to the souvenir shop I had encountered on my first day. The seller was standing, arms folded, with the expected mafia-like dignity. I bought postcards from him, and inquired about the boy who had guided me to the guesthouse. The man told me to wait while he looked around for him. When the boy finally arrived with a jumpy gait, a grin on his face, I greeted him with a pat of the cheek and said, “I want to meet your father. Can you take me to him?” He thought for a moment and said, “I go call him but take time.” “You take your time. Meet me at Cinema Rif.”

Grand Socco is the main commercial square of the medina. Like the famous Jemma El Fna in Marrakech, it was once populated with snake charmers and storytellers. The celebrated storytellers of Morocco who could captivate the crowds with tales from the Arabian nights and local folk legends are very much vanished. I could not find one even in Jemma El Fna, which transforms after sunset into a galaxy of clustered performances. By charging extra, a local guide had agreed to take me to a café curiously named Clock, where one of the last living storytellers gave weekly performances – in obvious hope of passing the baton to the young. Though I partially understood the tale between haphazard interpretations by the guide, the impromptu inventiveness of the old storyteller was at once beautiful and sad to watch, like witnessing the majesty of an ancient bird that is soon to get extinct. During the conflict years, when the likes of Burroughs and Layachi haunted the Grand Socco, oral storytelling was replaced by pleads and protests and harangues in the square, but the tradition’s amusing comebacks were never in shortage. In the book Morocco That Was, Walter Harris tells of an English preacher who delivered a fervent sermon in the square, whose firm instructions for salvation could get him in trouble had his wise, witty translator not changed the man’s serious words midair into a docile fairytale, thus keeping a largely non-Christian crowd from erupting!

Not even half as happening now, the outdoor seating at the Cinema Rif café still gives the best view of the beautifully palm-tree-outlined Grand Socco. It had become my usual place to be on evenings. I ordered three coffee cakes and listened to a man singing a very Arabic-infused rendition of “Every breath you take.” The boy’s father, when he shortly arrived, greeted me with genuine happiness. He was excited to meet someone from India and spoke a lot about Indian films from the 70s. He was a big Parveen Babi fan and missed her to this day. “No magic in new film… no spectacle like before,” he remarked when I asked whether he had seen any recent ones. Well in his 60s, his name was Driss, which I took to be Moroccan for Idris. “Hasan from second marriage,” he explained without my asking, sensing perhaps a curiosity on my part about their wider age gap. “My other boys very big. They working in Saudi.” Driss was wearing a baseball cap, which in a way explained Hasan’s love for caps, who quietly looked away as he ate his cake. After we had grown comfortable, I described what I wanted Driss to do, a task for which I was ready to give 200 dirhams. I had already quoted a decent amount so he had no cause to negotiate. “I not sure but will try,” he said, which was enough for me. We sealed the deal with a handshake. “I call on you when I have something,” Driss said and took his leave. Hasan, appearing bored and less cheerful in the company of his father, waved goodbye and carried his half-finished cake along.

Now that that was out of the way, I slowly sipped on a mint tea, taking my time with it while observing the many gatherings on the square, and decided on whim to catch a showing of Ernest and Celestine: A Trip to Gibberitia.

The first part of this beautifully animated French film series I had seen sometime in 2012 and with subtitles. There were none this time, but it was fun to interpret the story based solely on the visuals and the circumstances the bear and his rat friend were put through. Being in Tangier for these many days itself was a kind of estrangement for me, but it had become total in the cinema hall where I had to rely on cues of fellow viewers, their laughter for example, to know how to react to the film. It was as if I was cut off from everything and yet had access to everything. There seemed great freedom in this estrangement. After the show, exhilarated by the feeling, I walked faster and with eager steps through the medina. It put me in harmony with my earlier walks on the streets of other cities, walks that always make me feel as if I am about to end up with a new understanding of something, whatever it may be; walks that are only possible when a belief takes over, even if momentarily, that gravity has spared me. The lamp-lit white alleys of the medina became blank pages on which my legs could write any prose, no matter how outrageously senseless.

I tend to tire myself whenever I get into such a state, slowing down when my calves ache in protest and a happy dizziness washes me over. I stopped at a roadside joint whose fat proprietor, sitting on a stool with his hands resting on his thighs, asked, in the manner of a seasoned chef, what I would like to have. In the elation of the moment, my response turned out to be nothing short of dramatic: “make me a memorable meal, brother.” Breaking into an infectious smile, the man checked my diet preferences and offered a small glass of grapes juice, gesturing me to relax and get prepared to be surprised. Moments later, I was served a hearty assortment of harira soup, couscous tagine with stewed prunes, pine nuts and strawberry in honey, concluding with a concoction made by boiling figs with herbs found exclusively in the Rif Mountains.

Feeling stuffed, I strolled some more on the almost empty alleys. This was the first time I was out until midnight, but I enjoyed the understated beauty of Tangier at night. I thought of all those steps the streets here have borne for ages, of Ibn Battutah, of Paul Bowles, of Dassani, of the myriad humans who have come and gone looking for who knows what, and in the memory of these streets, I now add my own small footnote. The brightly lit harbor with the many docked ships, like any harbor in the world, was wonderful to look at from a distance, but to me that night it looked ethereal. I stood in the darkness of the Kasbah gate admiring it, allowing the night breeze to cool me down. That is when I became conscious of being completely on my own. My surroundings turned deserted the next moment. My mood shift from easygoingness to inexplicable eeriness was quick. I recalled a local legend Isaah had recounted a day or so before, of the gate being a haunt of the dangerous Aisha Kandisha. It is the same story in every culture, a beautiful woman calls out your name and if you as much as do an about face, she overpowers you. Of course, no one called my name during the brief time I stood there except, suddenly, a cone-headed thing emerged from out of the shadows, giving me the fright of my life. It turned out that the djellaba-clad man only wanted to sell hashish, but I darted for the guesthouse.

The Finnish anthropologist Edvard Westermarck has speculated that Aisha is the cultural remnant of Astarte, a goddess worshipped by the Carthaginians who founded Tangier, eventually integrated into Moroccan mythology. Later that night, as I lay awake with my crossed feet resting on the windowsill, I could not help read a subtext in the local legend, that of the inevitable disappointment all our pursuits run into. Follow her tempting calls if you will, the legend seems to say, but your joy is going to be short-lived. Not many nights ago in Fez, as I was buying packaged water from a store, the face of the girl on the counter had, almost unmindfully, bloomed into a heartbreaking smile, which in itself did not suggest anything but kept haunting me all night. It reminded me of a similar smile from my younger years, a smile that had suggested possibilities that did not exist. The wise have told us to be wary of Aisha Kandisha’s calls, which like the smiles from our pasts, are alluring but disappointing. My thoughts wandered to the woman in Mr. Gustav’s photographs. Some allure, some “call” must have brought both of them to Tangier; but now, as Isaah had said, “he is old Mr. Gustav who lives with a poodle.” Where did she go? What disappointment has made him live away from the mansion he has so lovingly built?

It was 4:30 AM when I became conscious of my room again. Did I really fall asleep or was just delirious with circular thoughts all night? I could not tell. There was an annoying heaviness in my head. I drank water and leaned out of the window. Sun was not out yet. I felt like having coffee but Isaah would not be up before 6 AM. I stepped out of the room to find the mansion in deep slumber. The bulb on the wall facing my room burned just enough for one to not run into obstacles. The two large hangings on the wall, one featuring the arc of Noah and another a colorful rendition of Al Buraq, were barely visible. I took watchful steps to make my way towards the kitchen. Had it been my first night, it would have been difficult for me to reach there, because after a series of winding stairs to reach the ground floor where the lounge was located, there was an unnoticeable gap on the right from where another stair led further down. The mansion was built on an inclined path, the Kasbah being on a hill, so there was an almost-hidden level in the mansion where the kitchen was located. I got down painstakingly because Isaah had not kept any lights on in these parts. I felt around for a switch. There was a door in the kitchen that opened to the lower part of the street, which I did not know. Like a blind man, I was feeling a wall when I heard a click and a creak. The kitchen door flung open and someone entered.

Shocked, the stranger and I both gasped in the dark, but soon light was turned on and a moment’s confusion later, it was understood that I was a mere guest while he was the owner. Mr. Gustav looked shorter in person. He wore a jacket and muffler over loose pants, and his carelessly swept-back white hair made him look like an absentminded professor. “Need something?” he asked politely while slipping the keys he had used in his jacket pocket, closing the kitchen door carefully behind him. I explained that it was too early to wake up Isaah so I was hoping to make coffee myself. Without saying anything, he approached the coffee maker and started making some. “Please don’t bother. It can wait,” I said, but he waved it off with a very zee-heavy English accent. “No bother. I myself need one.” A part of me was convinced that I was still asleep. “Sugar?” he asked. “Single cube please.” There was a table in the middle of the kitchen. We took a stool each and quietly sipped the milk-less beverage. It was way off from how I like mine, but my head was a heavy log and anything hot was most certainly welcome. “Say, is it usual for you to come this early?” I asked.

“No, no, only when I feel like it.” He went quiet after saying that. He was a slow man. He did everything slowly. He took his time with his coffee and he took his time with his words, pronouncing each neatly. “I was up all night and needed coffee,” he added. I began to ask something but did not know how. What had kept him up all night? Could he not make coffee where he lived? Must he do a full uphill climb all the way from Petit Socco this early just for a coffee? All I could say was, “Isaah told me you don’t stay here.” He smiled, as if that was obvious. Assuming a cheerful, appreciative tone, I declared, “You have a lovely place here. I wouldn’t stay away if I were you.” It made him look at me for long, then back again into his coffee. “Staying away makes me want to come back. Like for coffee.” Later, when going to be alone again, his response was to mean more to me than it meant in that moment. Mr. Gustav got up and began heating a pan. As was his overall demeanor, he brought out all the ingredients he needed with the graceful movements of a monk and placed his left palm on the side of the pan to feel the heat. “Scrambled eggs is a test of patience,” he said. He whisked the yolk and egg white into a consistent blend, and very slowly swirled the mixture with butter, making long delicate sweeps across the pan, taking care not to let curds form. It was very satisfying to watch. The creamy transformation of the eggs, seasoned only with chives, slid as soon as served over a toast, making Mr. Gustav quietly proclaim, “Just as it should be.”

Isaah woke me up around noon and said that he was waiting for me to come down for breakfast. I stayed silent trying to rub sleep off my face. Meeting Mr. Gustav earlier seemed like a dream. “Driss is here.” I got ready in haste and downed an entire pot of mint tea but only half-finished my breakfast, which was normally the most cherished meal of the day for me.

I walked with Driss a short way downhill to where his rusted fiat was parked. For the first time since I had arrived, going down the citadel housing the Ibn Battuta archives, down Grand Socco, down Gran Teatro Cervantes, down the fish market where Paul Bowles used to go shopping late at night to avoid crowds, as recorded by Michelle Green in The Dream at the End of the World, down the initial inclined road the cab I was in had taken many days ago, I had finally descended the hilltop Tangier medina. And it looked as though I had come down from another world, because the rest of Tangier, with its busy roads and modern glassy buildings, although broad and charming because of its close proximity to the sea, was like any other city. Driss drove past a huge shipyard and a school named after Socrates and stopped at a commercial compound. Many shops appeared to be in disuse. Some full to the brim with electronics goods. Few shopkeepers standing in small gatherings gave us curious looks. A man waved at and shared a joke with Driss. We walked past rows of shops, took some turns, and stood in front of one whose name read, Dassani & Co.

“Are you sure this is the one?” I asked.

“It an electronics shop,” Driss said. “Run by Indian.”

A shopkeeper next door informed us that the shop was closed for months. I wanted to know whether an old man ran it. “Old yes. Old man,” the shopkeeper said. “He has son but son left city long ago.” Why was the shop closed? “Don’t know. Man not coming many months.” Are you not well acquainted? “I don’t know very well. His shop very old. His shop so old he still sell videogame cartridge. Who buy them now? Many owners sell shop and move. I buy from daughter of a man who sell cloths. He was friend with this man.” I did not expect us to find the shop, and that too with an obvious name. In fact, I am not even sure what I was expecting when I had asked Driss to help me find it. I only knew that Dassani must be very old now and this one could very well be a different man. But I decided to take my chances. I wrote a note and requested the shopkeeper to hold onto it until Dassani showed up someday.

Mr. Dassani, you do not know me, but many many years ago, you met my grandfather. He was a young salesman from the state of Gujarat, and he believed that you were both in a train to Bombay. I just wanted to meet you and say hello. My grandfather would have been very happy to do the same.

By the time we got back to the car, I was choking with sadness. “Let’s not go to the guesthouse,” I said. “How far can you drive?” Driss frowned but he was thinking. “Tetuan. It white like Tangier. Good coffee.” Can you go farther? “I take you Chefchaouen.” Yes, let’s go there. Let’s go to Chefchaouen.

When not busy with his software development job, Jigar Brahmbhatt is either working on stories or reading fiction for The Bombay Literary Magazine as an editor. He loves to travel and divides his time between Mumbai and Gujarat.