Editorial: Issue 06/ June 2022

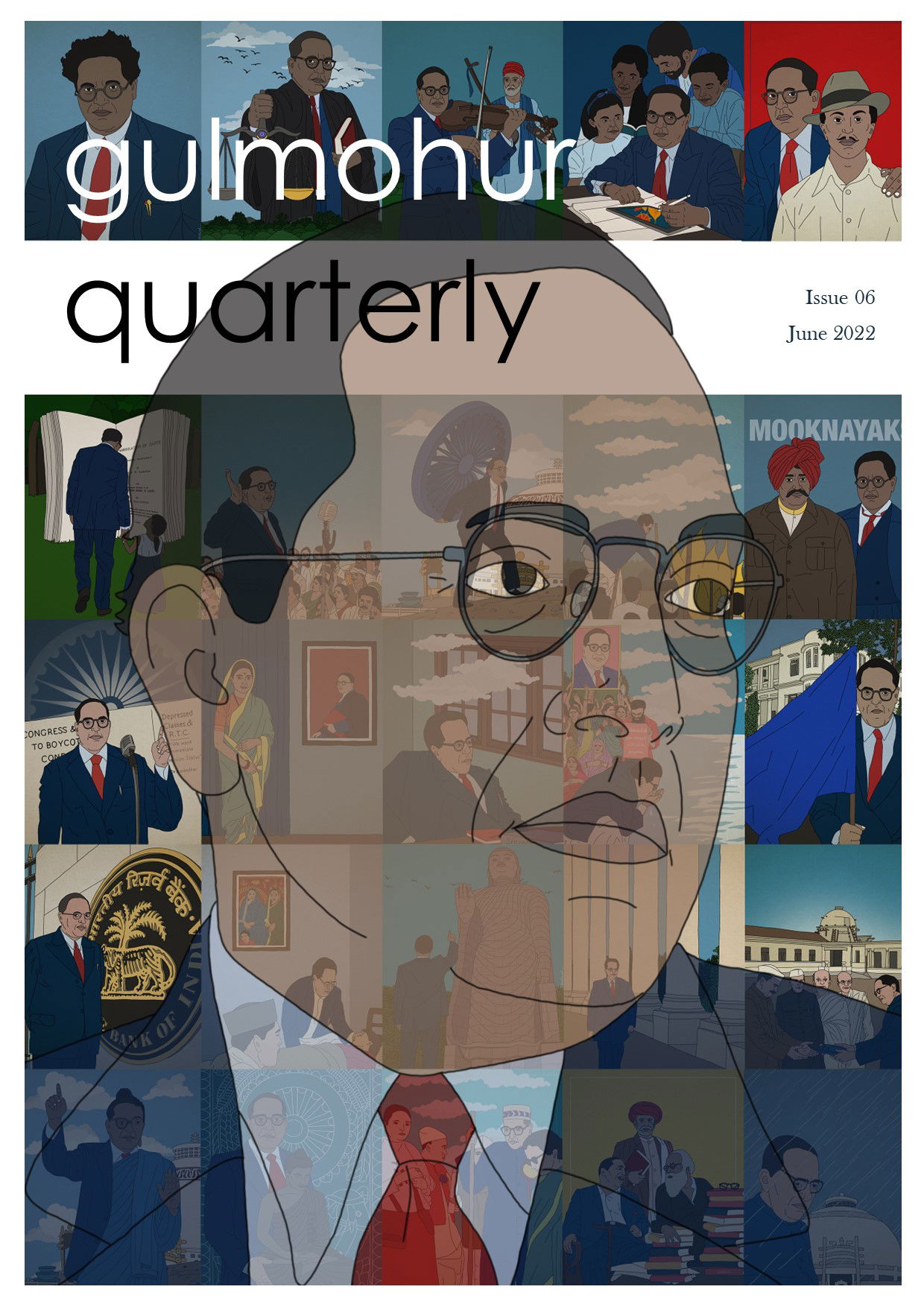

It is likely that you would stumble across our cover page on social media as you’re scrolling through images of state violence and videos with trigger warning, statements released and accountability demanded, hate justified and justice promised, raised fists and crumbled homes— when you notice the peculiar style of ‘Bakery Prasad’ and pause to admire the beauty of his work. Siddhesh Gautam was generous enough to give us this brilliant artwork for our cover this issue, which is an elegant display of his previous works and a fascinating engagement with Babasaheb. If you graze your eyes through the page, you’ll see Dr Ambedkar balancing the scales of justice, jamming with Kabir, surrounded by young children, placing his hand on the shoulder of Bhagat Singh, sharing space with Shahu Maharaj, Mahatma Phule, Savitrimai, Thanthai Periyar; Ambedkar with Buddha in various manners—looking up to him, carrying an idol celebrating him, and ultimately, transforming into the enlightened one; equally inspiring are the fiery moments of him speaking to his people, burning the Manusmriti, and of the Mahad satyagraha; we see him across architectural spaces of the parliament, a Buddhist stupa, near a window immersed in reflection, at the bedside, and in framed photographs looking from beyond; he has taken the Dhamma Chakra uphill on his back, he has held the blue flag of resistance, he is walking us towards the ‘Annihilation of Caste’.

Siddhesh’s colour palette is not extravagant and perhaps it brings a quality of calm and depth to his frames. Those blues seem to, every time we scroll past them, ask us to slow down and take the whole composition in, in order to study the eyes and the gestures, the emotions and the historical import of the scenes, the pain and love of the artist, too. On his Instagram @bakeryprasad, you’ll find Babasaheb, many well-known as well as obscure Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi figures from all over the country’s history, an engagement with contemporary issues, a voice of support going out against injustice anywhere, and most curiously, occasional self-portraits of the artist. Most of these posts are followed by reflective, agitated, educational texts. Siddhesh and a few other remarkable artists like him are consistently showing us the use of virtual platforms as mediums of resistance and collective assertions. Under the politics of it all, there’s a bold and affirmative aesthetics that gives shape to the works of these artists. This aesthetics is a movement unto itself, it’s a ‘becoming’ that we’re extremely proud of and look up to.

Siddhesh, in his short essay ‘The Art Side of Ambedkarism’, explains that the Ambedkarite movement has been consciously and unconsciously involved in working with symbols and aesthetic presentations of their own, which were “uncovered” by Babasheb himself. This is certainly a way of looking at “Dalit aesthetics”, a recognition that the mainstream is artificially narrow and doesn’t look and dig beyond its regulated ideas of the beautiful. Deeptha Achar, in her essay ‘Notes on Questions of Dalit Art’ makes a case for another approach towards understanding ‘Dalit art’:

Such a move, additive in its logic, imagines the idea of Dalit art as a preexisting body, hidden from view, needing to be uncovered and added to a mainstream corpus. However, such an argument hardly takes into account the function of existing frames, institutional structures and disciplinary apparatus that render the very possibility of Dalit art problematic. Instead, I propose to read the idea of Dalit art as a category in the making, speculated upon rather than actually ‘existing’. I believe such a framework enables us to conceptualise Dalit art as a process, an object in the process of becoming, one which in its very absence underlines the unmarked caste structures of modern Indian art (pp. 183-184, Dalit Text: Aesthetics and Politics Re-Imagined).

The mode in which the artist practices their art reveals something about the background against it which stands. It ‘brings to our attention’ the otherwise normalized gaze of savarna media and its projections, it states what it is like to experience and express in a different, non-parallel, ‘queer’ vocabulary. This movement in contemporary Indian art is becoming stronger and more self-confident (and self-aware) with every passing day; and it is a matter of great hope that a new kind of aesthetic vision is at work through these creative practitioners of art.

*

This issue contains an interesting range of translations. We’ve a brilliant satire by the Hindi writer Harishankar Parsai, which might as well have been titled ‘The (Savarna) Intellectual’. There’s an essay called ‘Mental Slavery’ by Rahul Sankrityayan which ought to be outdated by now, but isn’t, because of its seemingly simple and obvious illustration of the blindnesses of our grand civilization. You can also read the translations of brilliant poets from Punjabi, Bengali, and Hindi. You’ll find, in the Essay section, two curated entries on translations of Dalit-Bahujan poets from Hindi and Marathi, whose selections could give us a glimpse into the wealth of poetic expressions in the vernaculars of the oppressed. We hope this motivates you, readers, to explore literature in your own languages!

Besides, you will find a short-story around the gendered experience of harassment through a very familiar ‘gaze’, and another on a folk saying of the Khasi people. In the essay titled ‘No Home for Women’, you’ll find an articulation of the non-belongingness of women which is a systemic discrepancy and yet a norm; we’re asked to think about what our spaces mean to us and are brought back to the questions of how we inhabit, how we dwell. The poetry section in this issue ranges from the explicit outrage of injustice to the subtle ruminations of love. In ‘microaggressions’, the poet writes ‘maybe you won’t refuse to drink my water,/ since we’re friends and all, but my son will/ murk up the blood of your daughter?’ Another poet asks ‘Why Crack Jokes?’ with tongue not so much in cheek. One of the poems lists a few kinds of ‘loves’ through the final text messages of the lovers. In these pages, you’ll find words for losses and regrets, of the desire to let it all go and the urge to look back at it one final time, an ‘ennui’ and desolation, and words that crawl up to the corners of your heart and tug at something that reminds you why you read literature at all. Finally, the photo story in this issue is a ground-report of resistance by the people of Deocha-Pachami (and surrounding villages) in West Bengal against the DPDH coal mine project. As you look at these photographs, ask yourselves what we mean by development and how critical (or, conditioned) we are in our discussions about it. What do we need to be convinced of the voices of these protesting tribals? What prices do we demand for our ears to be sensitive to them?

*

gulmohur stands in solidarity with the jailed activists and intellectuals of the Bhima Koregaon case; the victims of communal hatred and of state violence; the victims of caste and gender violence; the victims of fundamentalist oppression anywhere in the world; and with all those who dissent in the spirit of democracy to safeguard our ever-diminishing freedoms.

*

We thank, once again, Siddhesh Gautam for his kind contribution to the magazine. We also thank our friends, Ambrish and Grishma, for their diligent works of translation. We extend our thanks to Tanmay and Malay for documenting the protest movement. We are immensely grateful to all our friends (on and off social media) who have helped us reach out. We also thank our contributors for trusting us with their submissions. We heartily thank our readers who make this endeavour so worth the effort.

We hope you continue enjoying this sixth issue of the quarterly. Please do comment your feedback to the authors on the webzine; and share the writings you like with people around you.

We wish you all a Happy Pride Month!

Editors

gulmohur

June 2022