Editorial: Issue 02/ June 2021

Words have limitations, which they have always had, but when thoughts fall short, evade validity and coherence, words move further away. Sometimes, they travel such distances that they cannot be recalled; those which return are reluctant to serve us. But they return, nevertheless.

What can a writer do about such uncanny returnees? Speak in a confused manner or become mute? Or is there another way out? Many ways, perhaps, hopefully. Not only for the writer but also for the reader; thereby enabling a world of possibilities that explores the prospects of a meaningful conversation through the medium of words, words alone.

But, from both, it also demands a ruthless sincerity in the pursuance of truths, which reveal themselves in the process of communicating, of reaching out to the other, exposing each other. These are truths that are subjective, personal, legitimate or not, but born out of our experiences and lived realities, sometimes in forms imaginative and fantastic, which no one can take away from us. These are our companions for life, whether they appear in the form of demons or butterflies, whether we are fascinated by them or disgusted, these are our lodgings- with or without windows and doors. Their vagueness, partiality, and incoherence, which may seem like a barrier, actually create a larger arena for interacting, stimulating empathy and understanding between the writer and the reader, the self and the world, between human and human. Anything less is a kind of pleasure-seeking, a voyeuristic temptation.

Toni Morrison wrote: “Literature has features that make it possible to experience the public without coercion and without submission. Literature refuses and disrupts passive or controlled consumption of the spectacle designed to nationalize identity in order to sell products. Literature allows us—no, demands of us—the experience of ourselves as multidimensional persons. And in so doing is far more necessary than it has ever been. As a simultaneous apprehension of human character in time, in context, in space, in metaphorical and expressive language, it organizes the disorienting influence of an excess of realities: heightened, virtual, mega, hyper, cyber, contingent, porous, and nostalgic. Finally, it can project an alleviated future” (Literature and Public Life).

The experience of ourselves as multidimensional persons forms the core of that arrangement on which literature stands. The structure that the writer has employed to carve her story, to reveal a fresh facet of human condition, to let you peep into her lodgings, is her gift to the reader. That is her way of sharing herself with the reader, an invitation to create a sacred space, to have an honest dialogue. This is where literature has the power to emancipate not just writers but its readers from their static realities, a thrust towards thinking more than one thinks, imagining more than one does; to “project an alleviated future.”

*

When we sat down to discuss this issue, the dilemma we faced was whether to publish this quarterly or to postpone. In the middle of this senseless devastation of lives and our worlds, augmented manifold by the same people who were to be responsible for its prevention, what purpose would this publication serve? What should we expect from our contributors? Should we fix a theme or a subject? What can we present to our readers? To sum it all up: what role does literature play in the face of a calamity so big?

Many responses can be arrayed in literature’s defense and many can be positioned to shoot them down. However, we can safely assume that these questions took birth with literature itself. The first time someone narrated a fictional tale, there must have been at least two people in the crowd who stood up and raised objections: “Why are you spinning lies?”; “Why should we listen to your fantasies?”. And sometimes a third, more reasonable and sensible than the rest: “Why are we wasting our time having this discussion when there is not enough food left for the season?”

We decided to publish this issue because we have more faith in literature than our cynicism and despair would allow us to have, because of our trust in the redemptive power of literature and arts, and the rare opportunity it offers– to (re)make sense of ourselves and this world, to raise it from the ashes (and now, not just metaphorically) and give it a new form and, hopefully, new names.

The past tragedies, which made a tremendous shift in the human psyche, also taught us that literature is the most notorious offspring of despair.

*

“Only one thing remained reachable, close and secure amid all losses: language. Yes, language. In spite of everything, it remained secure against loss. But it had to go through its own lack of answers, through terrifying silence, through the thousand darknesses of murderous speech. It went through. It gave me no words for what was happening, but went through it. Went through and could resurface, ‘enriched’ by it all.”

Paul Celan was one of the most influential German-language poets, who survived the Holocaust, which killed both his parents. It left an indelible mark on his memory and writing, and the trauma continued to haunt him till the very end of his life. When the problem of language and literature loomed large in discussions after World War II, Theodor Adorno famously declared that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” However, Celan proved that to write poetry after Auschwitz is not only possible but also necessary. Poetry must confront the catastrophe.

Last year, when migrant workers were desperately trying to reach home, it was a spectacle of epic proportions: thousands of them– men, women, children, old, sick, hungry, walking thousands of kilometers. It was unfolding right before our eyes and yet the television screen took it far away, so far away that to articulate its immense suffering, images from history and faraway lands were invoked. The bloody partition of 1947 was called its distant cousin and the Syrian refugee crisis was termed its contemporary equivalent. A year has passed since and what do we call it now? It was all possible because the ‘sense-making’ exercise was happening at a safe distance, safe enough that the language in which it was articulated did not betray the speaker and the listener.

The second wave of the virus has been less forgiving. It broke all the remaining barriers and pushed each one of us to a space that was equally unsafe and terrifying. The catastrophe that accompanied it had no analogy or past lookalikes anymore. It did not rhyme with slogans; it screamed in our ears and cruelly trampled on our bodies. It was no more a pandemic unfolding on TV screens, it was not about someone ‘else’, it had overlapped all such boundaries. It shattered that safe distance, from one side of which cliched commentaries could be written and #stayhome catchphrases could be fired. Suddenly, we found ourselves inhabiting the same planet.

At a safe distance we think safely, write safely. It is an illusion only some can afford and harbor but like all illusions, sooner or later, it shatters too. Before things settle down and we fall back to our old habits and initiate the process of forgetting, it is necessary to sit down in a quiet place and probe the thoughts we think and the language in which we express ourselves. As words begin to return, put them through a thorough interrogation and grill them till they speak what you couldn’t convey.

*

Right before the onset of the ‘second wave’, the digital space recorded an enthused celebration of Dalit History Month, in April 2021. We made an appeal in our call for submissions to invite writings from the Dalit-Bahujan experiences. We do realize that the nature of social media is not necessarily enabling or supportive when it comes to reaching out to the disadvantaged. There are remarkable people who are articulating caste experiences, on social media, and calling out caste prejudices in their many forms and are making a safe space possible. We sincerely hope that our future issues receive a growing number of entries from among the anti-caste voices and that we are able to facilitate a dialogue of agitation and resistance in more powerful ways.

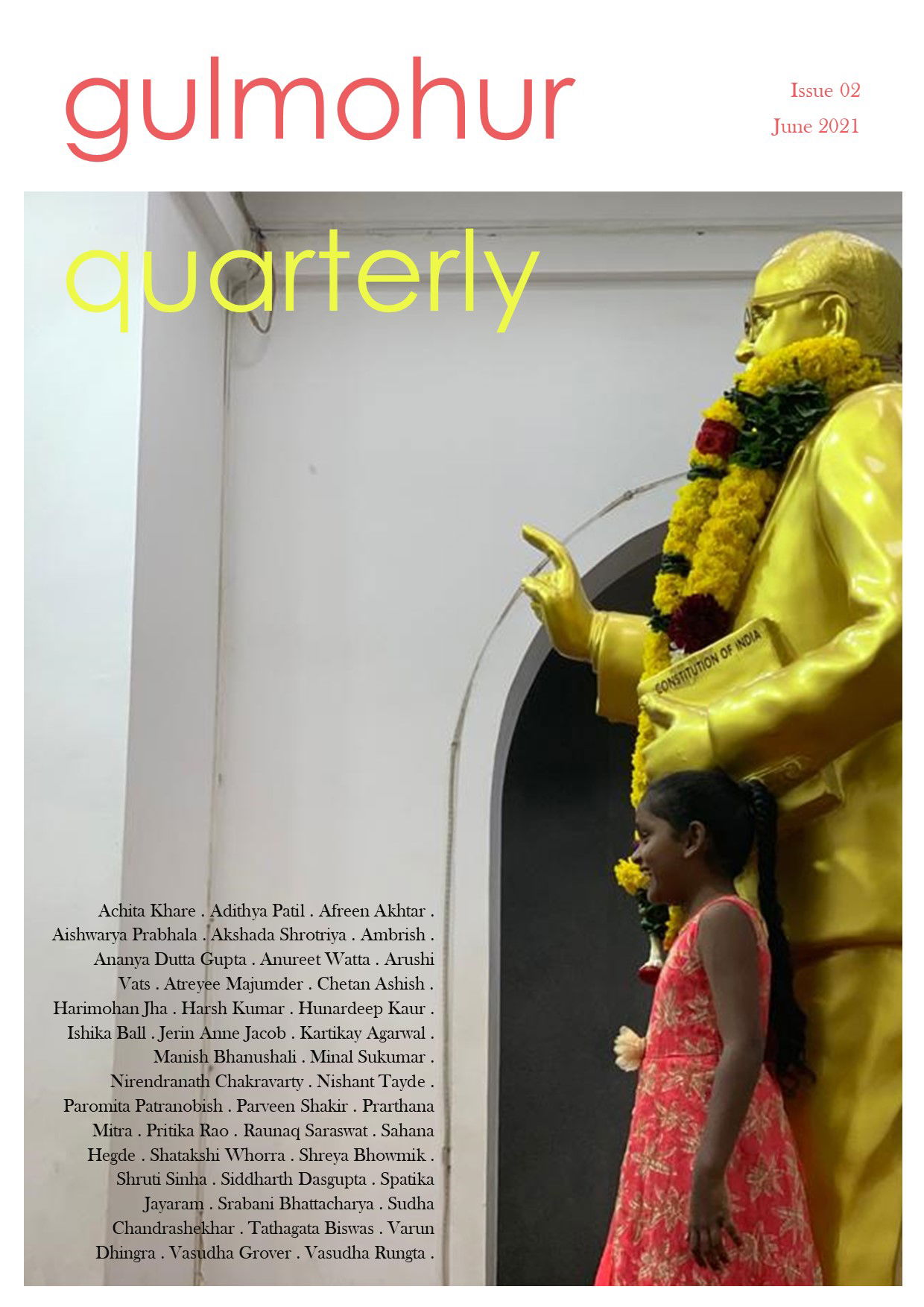

This issue features a Khattar Kaka short story by Harimohan Jha, which dismantles the edifice of Hindu scriptures in its scathing satire and critique. A poet refers to Ambedkar’s wait for the allegorical visa, and calls out the ‘protestors’ who grab more limelight than those really protesting. An essay interview of diaspora artist Kapil Seshasayee features his take on deploying anti-caste lyrics in his experimental music. A series of translations of a few Hindi poems by Adam Gondvi, Asang Ghosh, Surajpal Chauhan, frames the Dalit question in a direct and exasperated manner. The language of the gods, Sanskrit, is rejected and the literature of the savarnas exposed as nothing more than a chatterbox (gappi sahitya). The photo story documents the hard but determined lives of Tamil migrants in a Delhi settlement.

Another theme in this issue is that of the grave mismanagement of the ongoing pandemic and the fears and phobias, disgust and disillusionment, springing from it. One of the short stories gives us a glimpse of a future India which is at a geopolitical low, and locates its characters in the very setting of our year of the pandemic. Naturally, ‘the naked king’ is brought back to the public imagination and so are the references to the czars who plot with the vultures in a festival of death. A student describes the virtual experience of a classroom and the dawning reality of the two-dimensional screen-space, and questions what it means to be a student, minus the campus.

A poet brings to our gaze a painting called ‘Three Palestinian Boys’ and an academic reader articulates her reading of Olga Tokarczuk’s novel and offers her insights into the possible roles of literature in an ecology of interconnected realities. There is a fascinating curatorial work of translations of a few songs of the legendary Bengali band, Mohiner Ghoraguli. Besides, you’ll find in this issue, an eloping couple, a cheating husband, a secret parcel, Kolatkar’s butterfly and Frida’s watermelons, and many other excellent writings.

*

gulmohur stands in solidarity with the farmers’ movement against the farm laws, which has almost disappeared from news and yet continues; the victims of Israeli terror; the many arrested journalists; the jailed activists and intellectuals of the Bhima Koregaon case; the victims of caste and gender violence; the families of those who lost their loved ones to a systemic failure and mismanagement; and with all those who dissent in the spirit of democracy to safeguard our ever-diminishing freedoms.

*

We are extremely grateful to Ambrish for his brilliant work of translation and to Vasudha Grover for her contribution of the photo story. We also thank our friends, Aditi Bhande, Arundhati Dubey, and Sauvik Sen for their gracious help. We are immensely thankful for the help we received from people in reaching out on social media. Thanks are due to Aanchal Malhotra, Aathira Konikkara, Alolika Dutta, APPSC- IIT Bombay, Arunava Sinha, Bahujan Meme Page, Frustrated Indian Bahujan, Janice Pariat, Lisa Ray, Mahesh Rao, Marg Magazine, Meera Ganapathi, Open Call India, Orijit Sen, Seagull Books, Sharanya Manivannan, Shikhandin, Siddhesh Gautam, Smish Designs, Tara Anand, The Lit Archives, Varun Grover, and Walking Book Fairs. We also thank our past contributors and other friends who helped us spread the word which brought us an encouraging number of submissions. We thank all those who made submissions, too.

*

We have received kind words of appreciation from readers about our first issue. We welcome critical inputs and feedback for our work. We look forward to building an interactive platform to sustain our literary endeavours, with your generous support as readers. We hope you enjoy our second issue. Do share it with people around you. Finally, wishing you all a Happy Pride Month!

Editors

gulmohur

June 2021